LIBRARY HISTORY COLLECTION

Explore the history behind your local branch

about this collection

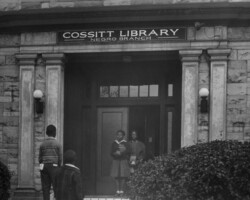

A lot has changed since the original Cossitt Library first opened its doors on April 12, 1893. The Library History Collection captures more than a century of development and progress, reflected in photographs, letters, and other documents.

Learn the history of the library below, and be sure to check out our Library Integration Collection, which contains contains legal documents, letters and news reports relating to the desegregation of Memphis Public Libraries.

Or, browse the collection for each library branch below, including our new Enhanced Branch Collections.

branch collections

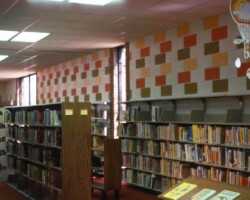

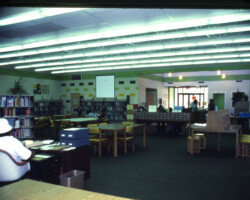

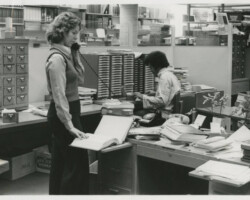

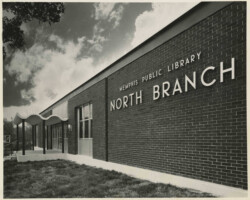

Ever wonder what your favorite local branch looked like 20 years ago? How about 50 years ago? Click an image below to browse the branch-specific collections and see how your library has changed through the years!

Browse our enhanced branch collections

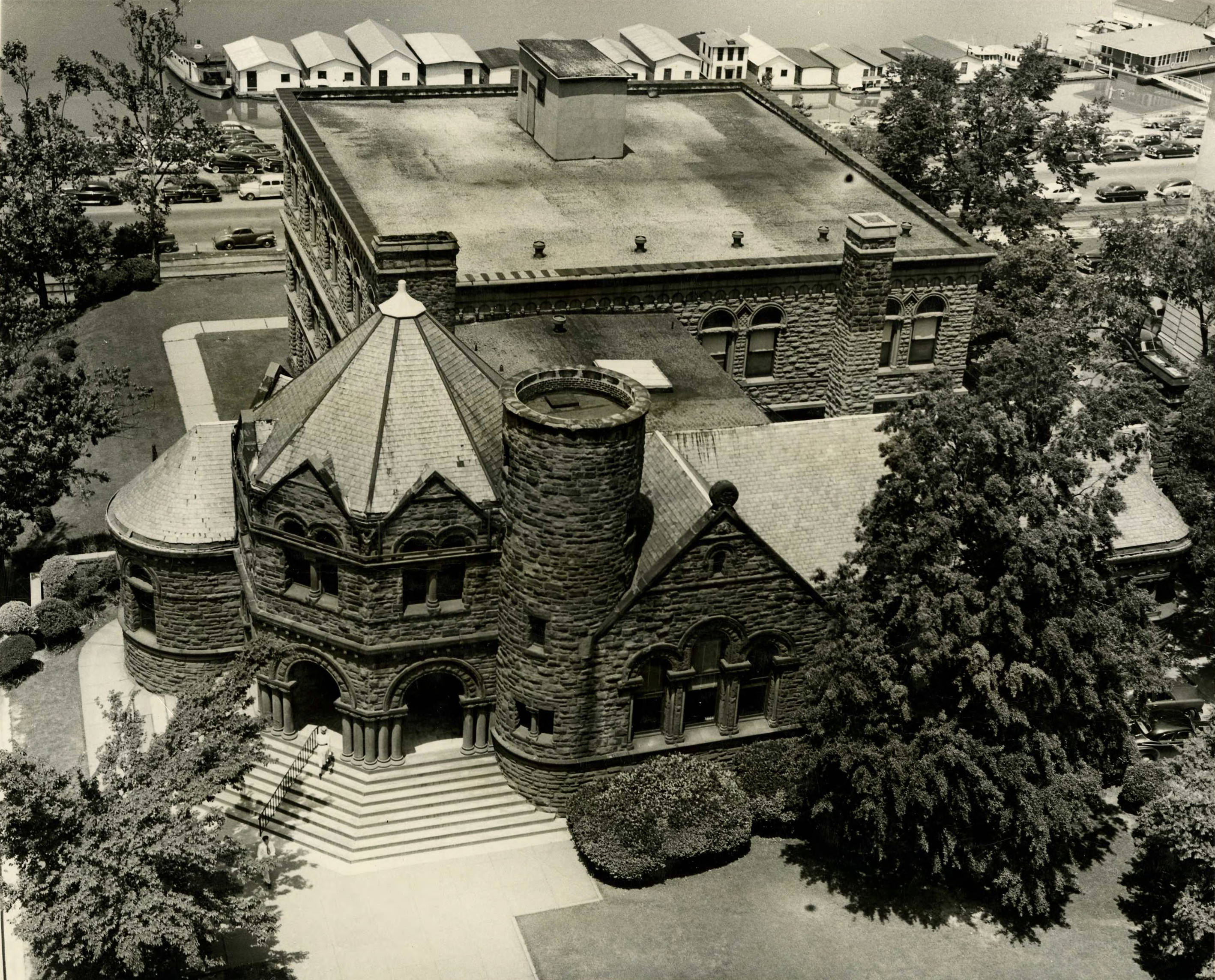

Cossitt Library

The history of public libraries in Memphis begins at 236 Front St, where Cossitt Library first opened its doors in 1893. At the building’s dedication, Reverend F.P. Davenport called Cossitt “the people’s university,” and for over 100 years Cossitt’s mission has responded to Memphis’s needs.

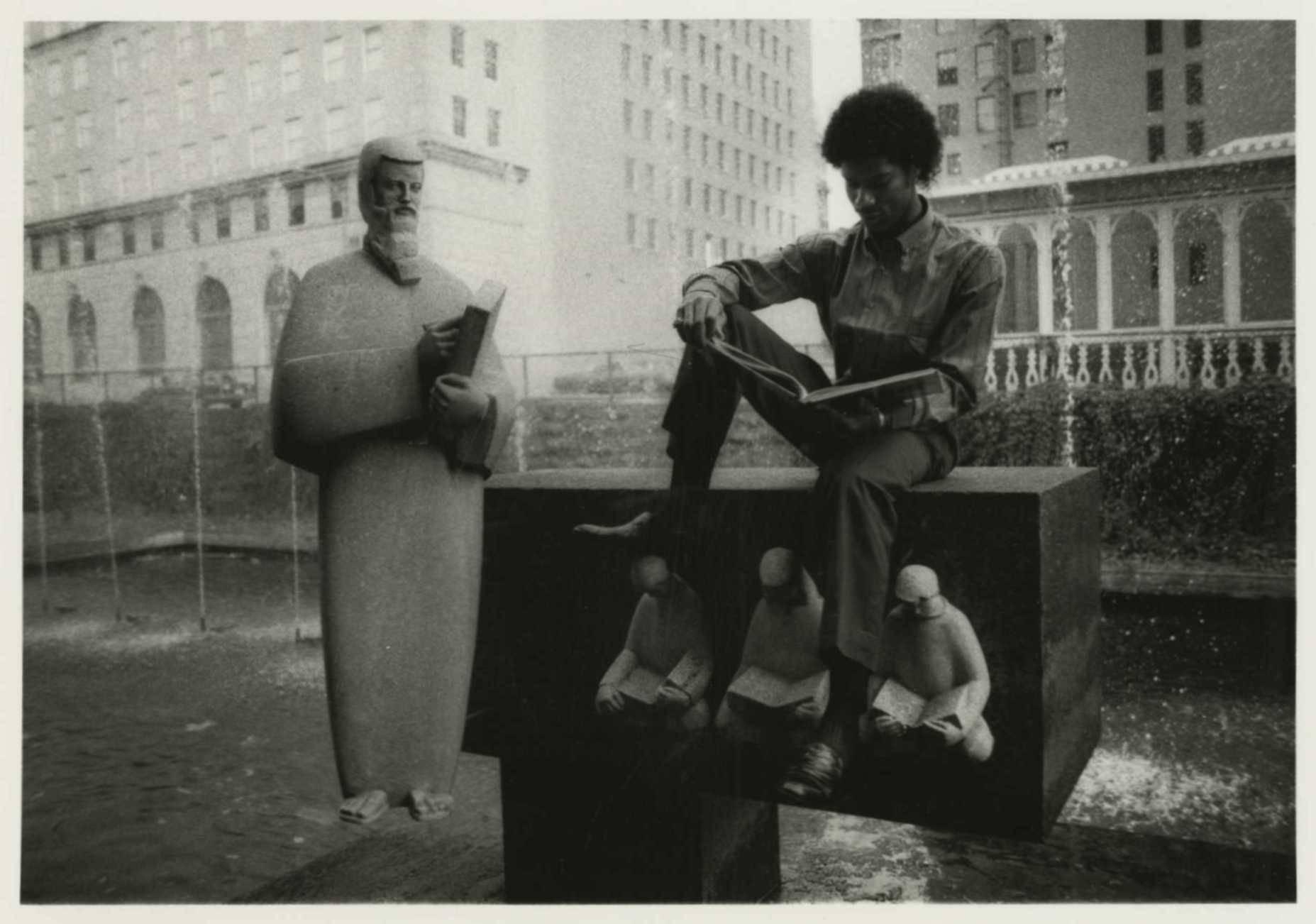

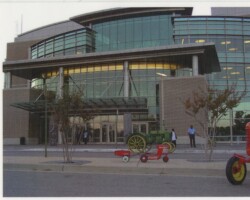

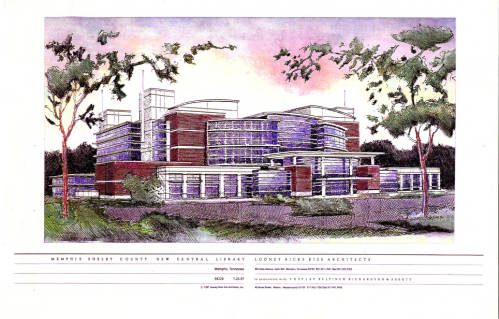

benjamin l. hooks central library

See how the “Library of Tomorrow” came to be and explore the public art installations in the Benjamin L. Hooks Library History Collection.

raleigh library

Explore Raleigh’s unique history through the digitized story-telling quilt that was on display at the Raleigh Library for years. Learn how the Raleigh Library was integral to the evolving community.

Memphis Public library Timeline

Explore the interactive timelines below to learn more about the history of the Memphis Public Library system.

To view the timeline full screen, CLICK HERE.

To view part two of the timeline full screen, CLICK HERE.

MORE INFORMATION

The Benjamin L. Hooks Central Library is the largest facility in the Memphis Public Library and Information Center system. Although opened in 2001, the history of Memphis Public began in the 1880s when the city received a $75,000 gift from the estate of merchant Frederick Cossitt to build a public library in honor of the city where he made his fortune. A section of public land near the Mississippi River was donated by City government who agreed to provide operating expenses for the library. With the promise of city funds it was decided that the entire $75,000 would be used for construction of the library building. As a result of this decision Architect L. B. Wheeler designed an elaborate Romanesque red sandstone building which opened on April 12, 1893.

Thousands of citizens attended the dedication ceremonies and toured the building but there was a problem. City government did not have enough funds for books and other research materials so the people were treated only to a beautiful, but empty, library building. Undaunted by this, the citizens of Memphis held fundraising events while the Cossitt family and financier Phillip R. Bohlen donated funds to purchase books. As the library shelves were being stocked with books the board of directors hired Mell Nunnally to serve as the first director of Cossitt Library. Serving until 1898, Nunnally oversaw the acquisition of the library’s book collection which expanded circulation to an average of 150 books per day.

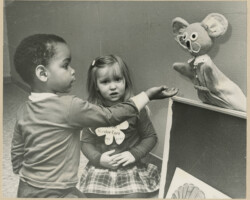

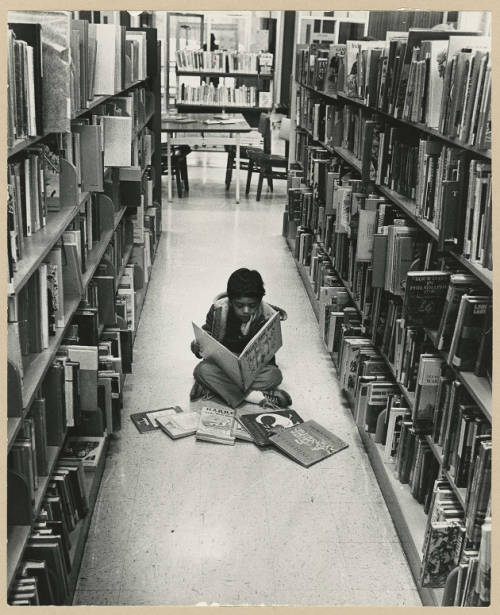

Inadequate public funding was the most important issue facing Nunnally’s successor, Charles Dutton Johnston, when he was named library director on September 1, 1898. Working assiduously with state and local government officials, Johnston was largely responsible for the Tennessee General Assembly passing a law which set aside a percentage of Memphis property tax revenue for library services. As a result of increased funding, Johnston established neighborhood libraries in storefront locations and public schools. An innovative librarian, Johnston created the children’s department in 1905 which expanded library services to young people. Due to Jim Crow segregation, Memphis African Americans were denied access to Cossitt Library but Johnston provided rudimentary library services to black Memphians when he opened a branch at LeMoyne Institute. Johnston also expanded the library’s infrastructure by adding shelf space and a reading room overlooking the Mississippi River in 1906 and securing a $150,000 bond issue from city government in 1923 to build an additional wing. As the three-story addition was being built on the west side of the library, Johnston fell ill and died on November 24, 1924.

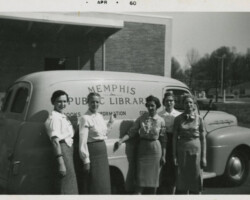

Jesse Cunningham, a graduate of the New York State Library School, was hired as director in March of 1925 two months after Johnston’s library renovations were complete. As a trained librarian, Cunningham introduced the Dewey Decimal System and other professional library standards to Memphis. In 1931, Cunningham secured a grant from the Julius Rosenwald Fund which established libraries in Shelby County schools and provided a bookmobile which delivered materials weekly to fifteen rural communities. Under Cunningham’s leadership a branch library system was created when the Vance Avenue branch for African Americans was opened in 1939 and the Highland branch and main library were built in 1951 and 1955. In addition, Cunningham oversaw a major renovation of Cossitt Library which regrettably led to the destruction of the 1893 red sandstone structure.

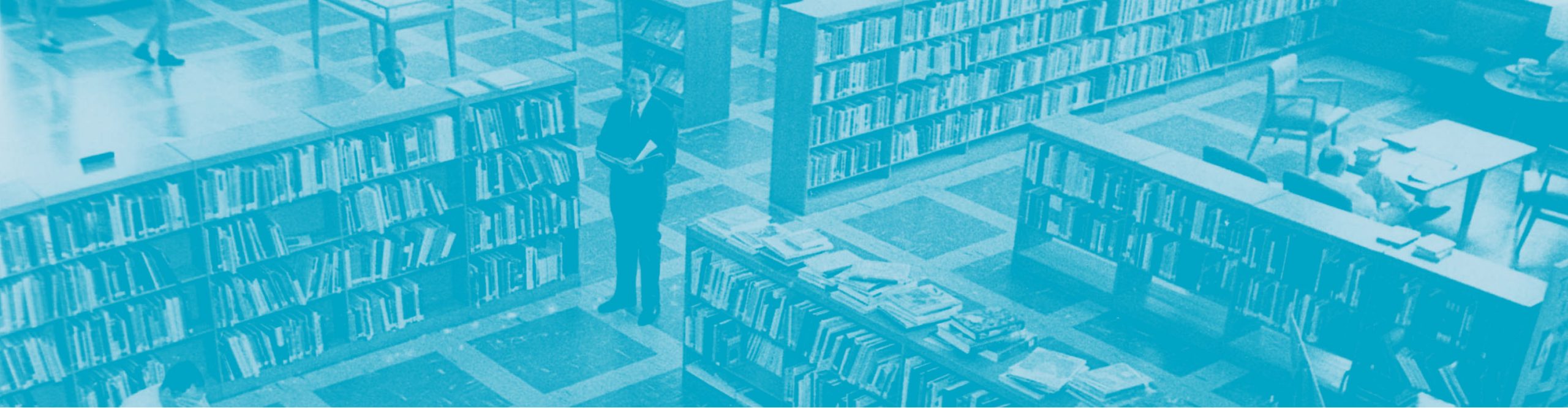

Creation of a county-wide library system continued under C. Lamar Wallis who was hired to replace the retiring Cunningham in 1958. Within ten years a branch was built in nearly every section of the city and county and in 1961 the privately-endowed Goodwyn Institute Library merged with Memphis Public to create a regionally-recognized business and technical collection. In 1973, city and county governments agreed to jointly fund local libraries which created the Memphis/Shelby County Public Library system.

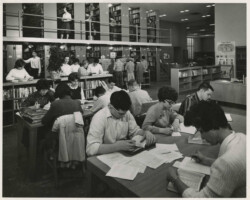

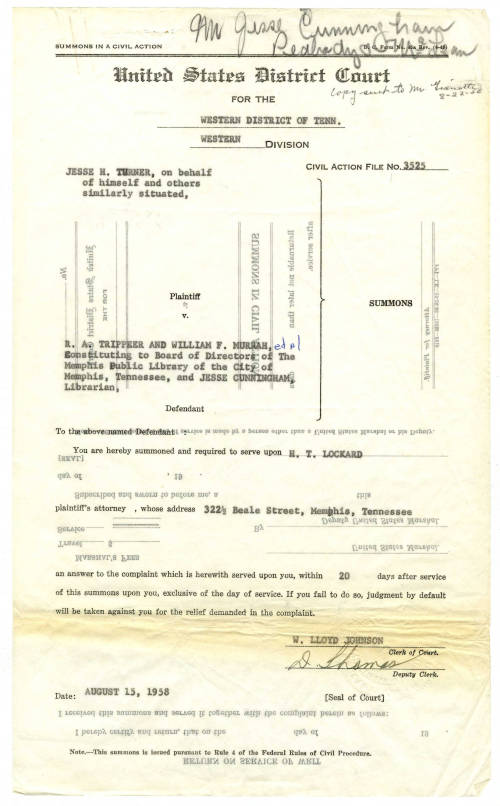

In addition to branch expansion, Wallis also dealt with the explosive issue of segregated library facilities. Memphis Public was sued in 1958 by Jesse Turner, an African American accountant who, like all black Memphians, was denied equal access to library materials and services. Turner’s lawsuit, combined with sit-in demonstrations by black college students, led to the desegregation of all public libraries on October 13, 1960. Integration was not the only controversy that surrounded Wallis’ tenure. In 1969, he received national attention when he refused to remove Phillip Roth’s novel Portnoy’s Complaint from library shelves when Mayor Henry Loeb objected to its contents. Wallis was awarded the Tennessee Library Association’s Freedom of Information Award for his dedication to intellectual freedom in 1998.

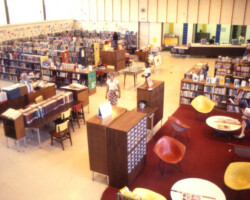

The commitment to innovation that emerged in the early 1900s continued throughout the 20th Century. An additional 80,000 square feet was added to Main Library in 1971, which afforded the space to create the Memphis and Shelby County Room local history collection and divide the reference collection into specialized subject departments. The creation of a countywide system, the development of the business and technical collection and subject department specialization led to the designation of Memphis Public as an information center in 1971. As a result of this emphasis on information delivery the Library Information Center (LINC) was established in 1975 to provide information and referral services to Memphians.

The organizer of the LINC department was Robert Croneberger who was named library director in 1980 upon the retirement of Lamar Wallis. In addition to continuing the information and referral program, perhaps the most important innovations introduced during the Cronberger era were the development of a radio reading service for the blind and a community information television channel. Over time these services were expanded into WYPL, the library’s 24-hour radio and television stations. Croneberger abruptly retired in December 1984 after only four years of service, a decision which led the board to hire its first female director in its ninety-year history.

Judith A. Drescher was hired as the sixth library director on June 21, 1985. Like her predecessors she was strongly committed to information services. “If libraries are going to promote themselves as an information service, they’re going to have to turn into one,” she said soon after her arrival. With this as her creed, Drescher brought library services to underserved neighborhoods through several mobile units and the construction of the Cordova and East Shelby branch libraries. The need for a modern centralized information center to replace the fifty-year-old main library was obvious to Drescher who worked assiduously for fifteen years to achieve this goal. This was secured when the Benjamin L. Hooks Central Library was opened to the public in November 2001. Three years later however, Memphis Public faced its greatest challenge since the 1890s when Shelby County government cut its library funding in July 2004. As a result four suburban branches withdrew from the Memphis Public system, effectively ending the countywide system created by Jesse Cunningham, expanded by Lamar Wallis and nurtured by Robert Croneberger and Judith Drescher.

Despite these setbacks, in 2007 Memphis Public was awarded the National Medal for Museum and Library Service by the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) for “extraordinary programs and involvement with the community.” One month later, in December 2007, Drescher announced her retirement after 23 years of dedicated service. Veteran city administrator Keenon McCloy was appointed director of libraries in 2008. Under McCloy’s leadership the library system was made a part of Memphis city government’s Public Services and Neighborhoods Division and thus was fully integrated with municipal operations. In addition, procedures were streamlined to better serve the citizens of Memphis.

As the awarding of the IMLS National medal suggests, a strong commitment to information delivery, community outreach, and an innovative approach to library science remain the core principles of the Memphis Public Library and Information Center, just as it did when the library was founded in 1893.

– G. Wayne Dowdy, Hidden History of Memphis