The Road to Ratification

“If Delaware does not ratify the suffrage amendment we will go to Chicago and demand the reason why. I will walk to Chicago if necessary to make our views and protests known. There are plenty of women who would join me.”

— Mrs. Benigna Green Kalb, Houston, TX, from Women to Camp on Republican Trail, Commercial Appeal May 20, 1920.

WHO WILL BE THE 36TH?

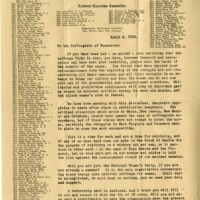

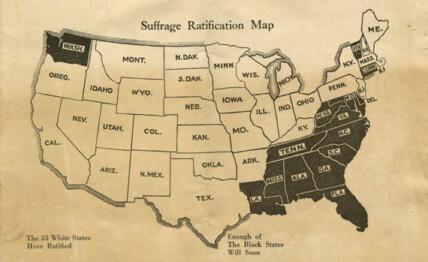

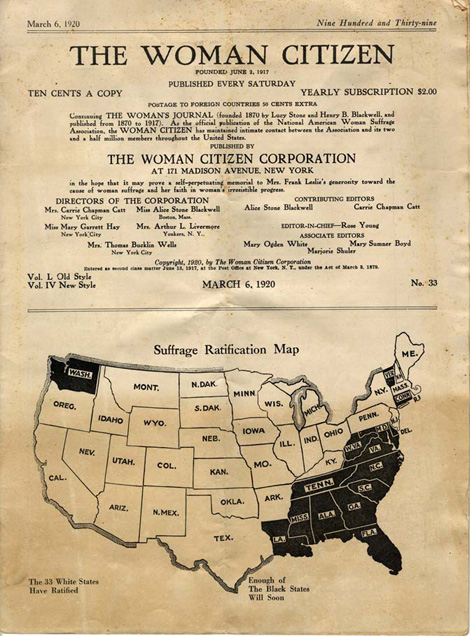

In the early states, the amendment breezed through. Within a month, nine had ratified. In another month, five more joined. However, there were defeats, mostly in the South. Georgia was the first state to reject ratification, with Alabama, Carolina, Virginia, and Mississippi soon following their lead. To stop the defeats, prominent suffragists like Carrie Chapman Catt and Alice Paul went on the offensive, dispatching teams of organizers to states that were slow to ratify.

“How long must women wait for liberty?”

Banner carried by suffrage pioneers, Rev. Olympia Brown and Mrs. Anna Kendall, from Women Will Picket Chicago Convention, Commercial Appeal June 7, 1920.

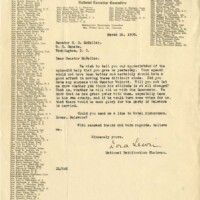

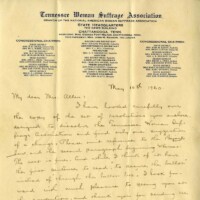

The plan was to whip up local support, energizing activists who could then take the fight directly to their state legislature. Catt, in particular, tried to project a positive front, making a distinct effort to give the impression that ratification was just a matter of time. They also enlisted the help of nationally notable politicians like President Woodrow Wilson and Tennessee senator Kenneth McKellar. Being one of the few ardently pro-suffrage southern Democrats, McKellar was a rare commodity in a region hostile to the suffrage movement.

President Wilson, the first southern born president since before the Civil War, used his influence to prod less than enthusiastic Democratic governors to call their state legislatures into session to approve the amendment. Repeatedly pushed by pro-suffrage forces, Tennessee governor Albert Roberts had been hiding behind the convenient political excuse that his state’s constitution prevented the legislature from considering the amendment until after the fall elections.

By the end of March 1920, the total number of states having ratified stood at thirty five, one short of the required three-fourths to make the amendment a permanent addition to the Constitution.

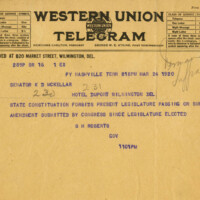

Senator McKellar, a Memphian, had watched with concern as the ratification effort failed in Alabama and Virginia. Now as the suffrage movement targeted Delaware, he waded into the fray. He also kept tabs on the push for ratification in Louisiana, where the governor had pledged to block ratification.

Pro-suffrage governor of Delaware, John G. Townsend, called his state’s legislature into a special session. Unfortunately, the effort backfired when the amendment stalled during a procedural vote, allowing anti-suffrage forces to claim an upset victory in a state that had seemed sure to ratify.

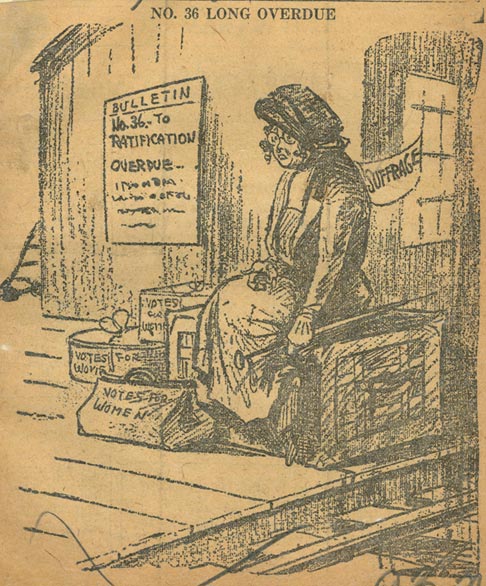

A political cartoon published in the Baltimore Evening Sun showing a woman sitting on a trunk at a train station with her luggage around her labeled “Votes for Women” and a bulletin on the wall that reads “No. 36 to Ratification Overdue,” comparing ratification of the 19th Amendment to a train running late. Women’s Suffrage in Tennessee, Tennessee State Library and Archives ID# 45410.

Things only got worse. In July, Louisiana rejected ratification as well. Though not a surprise, the defeat came at a poor time. It conveyed the impression that ratification might be going backward, an idea that those opposed to women’s suffrage were keen to magnify. In the South, Florida and North Carolina seemed unlikely to ratify. And in the North, rabidly anti-suffrage governors in Connecticut and Vermont refused to convene their state legislatures for special sessions.

Luckily, a decision by the U.S. Supreme Court regarding a different constitutional amendment opened up a new front in the ratification fight and offered the suffrage movement an unexpected chance to grab the thirty-sixth state. In a lawsuit involving the Eighteenth Amendment, the court ruled that no state law could obstruct the ratification of a constitutional amendment. For the suffrage leaders, this immediately changed the political landscape. Specifically, it put Tennessee back in play. Governor Albert Roberts could no longer claim that the state’s constitution prohibited him from calling a special session of the legislature to consider the amendment. Still, facing a difficult re-election, Governor Roberts was reluctant to engage in the political battle over women’s suffrage.

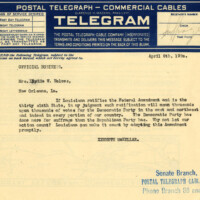

Suffragists like Catherine Talty Kenny of Nashville deployed strategic political pressure by getting the White House to intervene. Extremely popular in the overwhelmingly Democratic South, Wilson sent a telegram to the governor urging him to do, “a real service to the party and to the nation”. When Roberts continued to stall, the president went public with his frustration. Sufficiently chastised, the governor relented and called a special session, convening the Tennessee’ legislature to consider the amendment granting women the right to vote.

ITEMS FROM THE COLLECTION