On the Ground in the Bluff City

“Even those signs as in Memphis and other cities, in windows, on business streets, helped to awaken thought and questions on the subject of the Constitutional needs.”

— Martha E. Allen from Report for 1916 State Convention at Nashville, Tenn.

MEMPHIS AND WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE

As the state’s largest city, Memphis played a major role in getting the 19th Amendment ratified by the State of Tennessee. In fact, Memphis became the main bastion of support for suffrage within the state during the ratification fight in 1920. Virtually all the state legislators from Shelby County voted in favor of women’s suffrage.

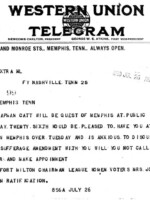

“We cannot be over sanguine and stop work therefore we are urging you, our friend, to double your efforts until victory is won.”

Letter from Memphis Equal Suffrage League to Senator McKellar, 1919

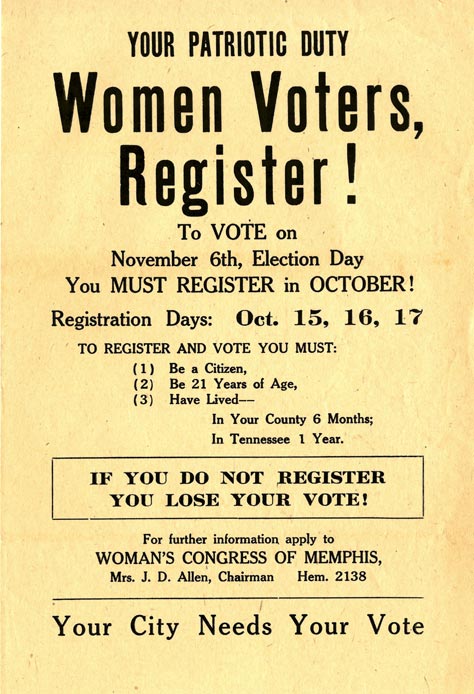

Flyer from the Woman’s Congress of Memphis, an organization created in 1919 in response to a newly passed state law granting women the right to vote in presidential and municipal elections. In response, local suffragists organized to encourage women’s participation in the electoral process. Mentioned in the flyer is the president of the organization Martha Allen, referred to here as Mrs. J.D. Allen. The M Files Collection, DIG MEMPHIS, Digital ID Suffrage0006.

Starting in the 1870s, women in Memphis began to build a network of clubs and institutions that would eventually culminate in the creation of a local suffrage organization in 1889. Societies and institutions like the Women’s Christian Association (WCA) and the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) gave local women avenues to participate indirectly in city politics without overtly violating the traditions of the time.

During this period, openly advocating women’s suffrage required extraordinary personal courage due to widespread social taboos discouraging women from getting involved in politics. Inspired by Susan B. Anthony’s 1872 arrest and trial for attempting to vote, local social reformer Elizabeth Avery Meriwether attempted to vote in the 1876 presidential election. Local authorities did not arrest Meriwether, partially because it is likely election officials, who were family friends, destroyed her ballot.

Beginning with educational institutions, such as schools run by Clara Conway and Jenny Higbee, reform minded women in Memphis slowly expanded the definition of what was acceptable female behavior. Lide Meriwether, Elizabeth Avery Meriwether’s sister-in-law, tackled issues like prohibition and prostitution. While local socialite, Elise Massey Selden, founded the Nineteenth Century Club, an influential local women’s organization that eventually fought for and won reforms in sanitation, education, and law enforcement. Prohibition was so interwoven with the early development of the women’s suffrage movement in Memphis that they were virtually synonymous. In fact, the local chapter of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) voted to make obtaining women’s suffrage one of their objectives before there ever was a local suffrage organization.

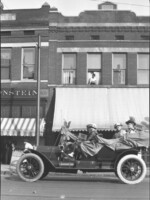

In 1904, the Equal Suffrage Association was founded in Memphis. That Association soon failed due to lack of funds, but in 1906 Memphis women organized the Equal Suffrage League and named Mrs. Martha E. Allen (also referred to as Mrs. J.D. Allen) as their first president, a role she held until 1912. During this time Allen worked to organize the women’s suffrage movement in Memphis and throughout the state of Tennessee. These efforts included countless parades, rallies, pink teas, flying of flags, and rummage sales. Her efforts paid off and she later earned the honor of being called the grandmother of the Memphis League of Women Voters.

This portrait shows a group of women, each wearing a badge of some sort. Given the nature of the J.B. Mann Suffrage Collection it seems likely that this group of women was involved in some sort of suffrage activity. The M Files Collection, DIG MEMPHIS, Digital ID Suffrage005.

Meanwhile, local women broke professional barriers that had oftentimes held them back for years. Marion Scudder Griffin, after having been twice denied a law license because of her sex, petitioned the state legislature to allow women to become attorneys. Lawmakers initially greeted her proposal with laughter; nevertheless, she persisted and eventually convinced the legislature to pass a bill allowing women the right to practice law. In 1907, she became Tennessee’s first female lawyer. Lula Colyar Reese, a member of Alice Paul’s National Woman’s Party, became one of the first women elected to the Memphis school board and later served as president of the Nineteenth Century Club.

In the state legislature, suffragists won gradual concessions on women’s rights, including the right to control their own property after marriage. In 1919, the state legislature decided to give women the right to cast ballots in certain elections. Women could participate in municipal elections and the U.S. presidential election, but they could not cast ballots for governor, the state legislature, or congress.

This partial enfranchisement came just as other states began to ratify the 19th Amendment, though it seemed unlikely at the time that Tennessee, not having granted women full voting rights before, would ratify anytime soon.

ITEMS FROM THE COLLECTION