The Fight in Nashville

“ We are rejoicing over the results of our work so far, but we intend to continue just as strenuously during the two weeks intervening before the special session because we want the vote for ratification to be as nearly unanimous as possible.”

— Abby Crawford Milton from Noted Suffragist to Visit Memphis Today, Commercial Appeal, July 26, 1920.

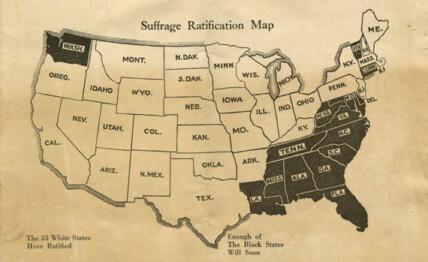

WILL TENNESSEE RATIFY?

With Tennessee back in play, political forces from all sides bore down on Nashville, focusing intense political pressure on the state legislature who could ultimately decide whether to give women across the country the ballot or not.

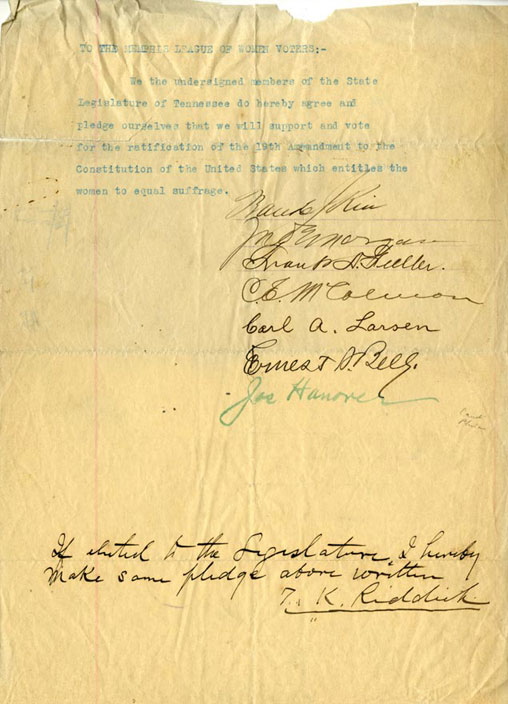

“SHELBY DELEGATION IS READY TO RATIFY. Legislators Sign Pledge to Work for Suffrage.”

Commercial Appeal, July 29, 1920.

At the outset, Carrie Chapman Catt did not have much hope for Tennessee. As part of the South, a region that had generally proven unfriendly terrain for suffrage, the state had only recently given women the right to participate in any elections at all. Beyond that, many of Tennessee’s neighboring southern states had already rejected the Nineteenth Amendment due to concerns about potential federal oversight, which could undermine the system of Jim Crow laws that kept white supremacy in place in the region.

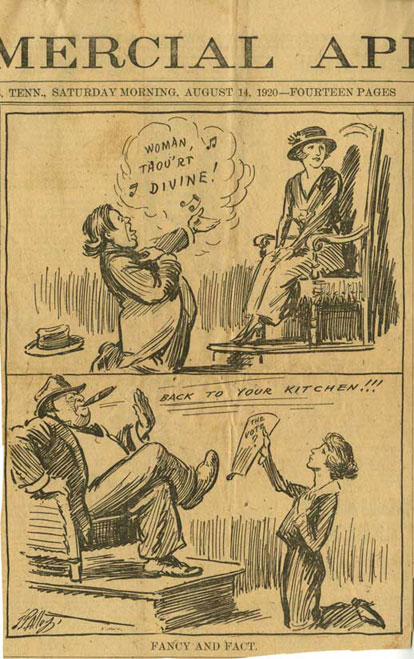

Before the start of the legislative session, House Speaker Seth Walker, who had previously pledged to support ratification, switched sides. Labeled a traitor by suffragists like Betty Gram, Walker devoted his considerable political skill to the anti-suffrage cause, as did his friend the House Majority Leader, William Bond.

In East Tennessee, Republican legislators were largely divided. Under pressure from the Republican National Committee, the state party had openly declared support for ratification and encouraged legislators to do the same. However, there were holdouts. For example, Herschel Candler, a long serving state senator, and his protege representative Harry Burn had both voiced opposition to ratification.

In West Tennessee, legislators from Memphis and Shelby County formed a solid phalanx of support for ratification, thanks in part to local political boss E.H. Crump, whose wife Bessie Crump was staunchly pro-suffrage. However, local support went beyond the city’s political machine. For instance, Mayor Rowlett Paine, a political independent, had openly declared his support for women’s suffrage by agreeing to serve on the statewide Men’s Ratification Committee, as had editor C.P.J. Mooney of the Commercial Appeal, who fiercely hated Crump.

The city sent an enthusiastic contingent from the local chapter of the League of Women Voters to Nashville. At their head was school superintendent Charl Williams, who had recently become the first woman to be made a national vice chair of a major political party. She would serve as an intermediary between the various factions supporting ratification.

Joe Hanover, who represented the Binghampton neighborhood in Memphis, served as floor leader for the pro-suffrage legislators in the Tennessee House of Representatives. Working tirelessly, he lost nearly twenty pounds during the battle over the Nineteenth Amendment. During the session, the governor assigned him a police escort due to threats against him.

At the start of the session, the suffrage amendment fared well in the Senate. It took only five days for it to pass by a wide margin despite stiff opposition from a few holdouts. However, it struggled in the House. There, legislators opposed to the amendment fought a war of delay, making strategic use of parliamentary procedure at critical points as the pro-suffrage side tried to advance the measure. The goal was to run out the clock, forcing the proposed constitutional amendment to die a death of a thousand delays until the energy behind the push for women’s suffrage evaporated.

Both pro-suffrage and anti-suffrage activists went to work to hold together their coalitions. Simultaneously, they tried to cause defections on the opposing side. Unfortunately, these efforts created confusion on the political battlefield. Multiple legislators had at different times pledged support for either side, and no one could be sure how firm those pledges were until actual votes occurred. As many battle hardened suffragists knew all too well, once the amendment went up for a vote, surprises could happen.

In fact, that was what Seth Walker counted on, hoping to bring the suffrage amendment to a vote at a moment when support was weakest, so he could kill it. As Speaker of the House and leader of the anti-suffrage faction, he could essentially force a vote on the issue. This made it even more important for the suffragists to maintain a majority, and to do their best to bluff when they couldn’t. Unfortunately, a week into the session, five of seven members from Davidson County that had pledged to ratify went over to the antis. By the suffragists own count, they were two votes short of a majority.

Sensing weakness, Walker pounced. Calling for a vote on ratification, he hoped to bring the issue to a final head. With the Davidson County defections, the antis held the majority, or at least, they appeared to. As the vote unfolded, it became clear that efforts to convert supporters had not just affected the suffragists. Two legislators broke ranks with the antis, and it became obvious that Walker and the anti-suffragists had miscalculated.

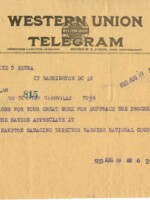

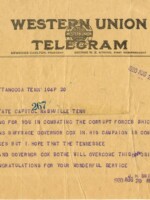

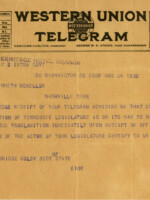

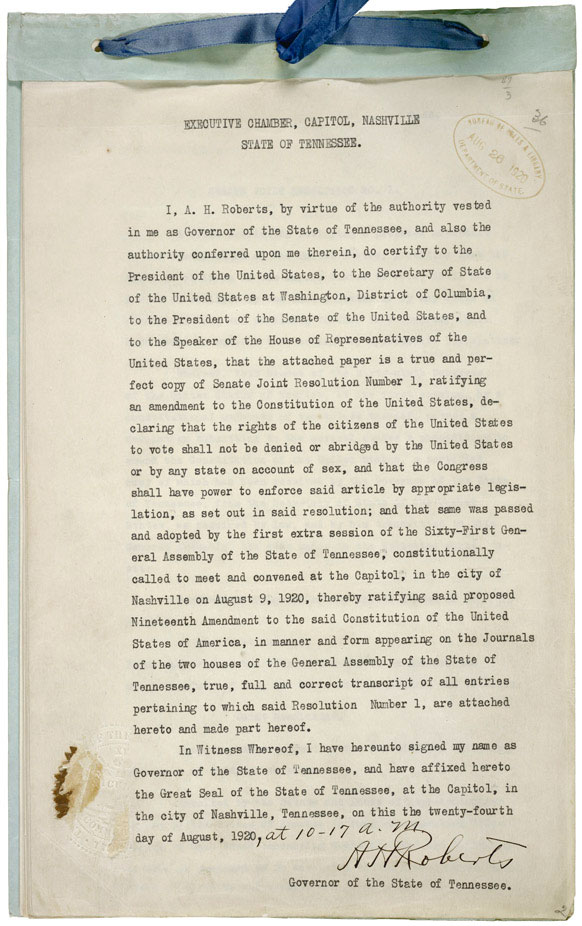

Tennessee ratified the amendment on August 18, 1920. Almost immediately, congratulatory messages flooded in, as suffragists across the country, some of whom had fought for decades, celebrated.

At the same time, anti-suffrage forces launched last ditch efforts to overturn ratification. In the press, they alleged that Joe Hanover, leader of the suffrage forces, had bribed Harry Burn, an East Tennessee legislator who switched sides at the last minute. They also initiated court challenges, hoping to stall.

None of it mattered. Despite the antis protests, Governor Roberts signed the state’s certificate of ratification with Memphis suffragist Charl Williams standing by his side. Within two days, United States Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby signed the documents finally putting the Nineteenth Amendment into effect on August 26, 1920.

With a stroke, the amendment enfranchised millions of women across the country. Since the Civil War, nothing had granted such freedom to so many with such speed. For many, it was the culmination of countless personal sacrifices and politically bloody battles waged for the better part of a century by women across generations.

ITEMS FROM THE COLLECTION