Women’s Suffrage and Race

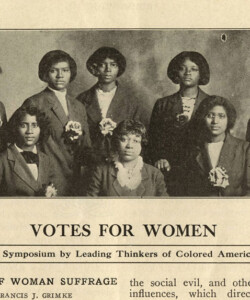

“Seeking no favor because of their color, begging for nothing they do not deserve, they knock at the door of justice and ask for an equal chance.”

— Mary Church Terrell from “The Progress and Problems of Colored Women”

RACIAL INJUSTICE WITHIN THE MOVEMENT

Beginning in the 1840s, the movement for women’s suffrage in the United States originated as an offshoot of the struggle against slavery. Many early women’s suffrage leaders identified as abolitionists and extended the logic of universal liberty to include women’s rights. Female abolitionists, such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Sojourner Truth, saw an opportunity for the country to grant both African Americans and women the right to vote. Unfortunately, the amendments enacted during reconstruction defined voting rights as belonging to “male citizens”, the language a deliberate calculation by abolitionist leaders that feared combing the two goals would be too difficult politically. The result contributed to a break between the two movements.

“If judged by the depths from which they have come, rather than by the heights to which those blessed with centuries of opportunities have attained, colored women need not hang their heads in shame. … I dare assert, not boastfully, but with pardonable pride, I hope, that the progress they have made and the work they have accomplished, will bear a favorable comparison at least with that of their more fortunate sisters.”

Mary Church Terrell, from The progress of colored women, February 18, 1898

From left to right: Josiah T. Settle, Fannie Settle, Mary Church Terrell, Robert R. Church Sr., and Anne Wright Church. Mary Church Terrell was a well-known activist and leader in the women’s suffrage movement. She founded the National Association of Colored Women and wrote about her activism for both women’s suffrage and racial justice in her autobiography, A Colored Woman in a White World. The M Files Collection, DIG MEMPHIS Digital ID RCC0002.

With the resurgence of the South in American politics after Reconstruction, leaders within the suffrage movement like Anthony and Stanton distanced themselves from their former anti-slavery colleagues and adopted a southern strategy to win the vote for women. This strategy involved assuaging the fears of white southerners that women’s suffrage would threaten the system of Jim Crow laws that disenfranchised African Americans in the region.

In Memphis, some of the earliest supporters of women’s suffrage were the wives of former Confederate officers. Elizabeth Avery Meriwether, whose husband served under Nathan Bedford Forrest, was both an enthusiastic advocate of women’s suffrage and proponent of the lost cause mythology that glorified the antebellum South.

In that cultural climate, the strategy employed by suffrage leaders drastically limited the opportunities for African American women to participate in the suffrage movement. When the National American Woman Suffrage Association held a convention in Atlanta in 1895, Susan B. Anthony personally asked Frederick Douglass, who’d been a long time supporter of women’s suffrage, not to attend. Explaining the decision to a young Ida B. Wells, Anthony was blunt, “I did not want to subject him to humiliation, and I did not want anything to get in the way of bringing the Southern white women into our suffrage association now that their interest had been awakened.”

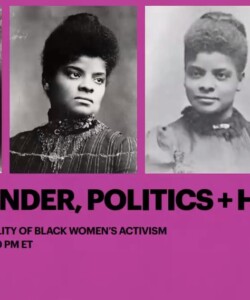

In another notorious episode, both Wells and Mary Church Terrell, president of the National Association of Colored Women and co-founder of the NAACP, were asked to march at the back of a 1913 parade for women’s suffrage in Washington, D.C. Wells, despite being told she could not march with her state delegation, snuck into the parade and marched with them anyway.

Black women organized clubs advocating for women’s rights and other social causes within community. In Memphis, they formed a separate chapter of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), an organization advocating prohibition. Educator Julia Britton Hooks established multiple organizations, notably the Orphans and Old Folks Home, the Phyllis Wheatley Union, and the Hooks School Association. While it’s unclear whether Hooks had a role in its founding, the Coterie Migratory Assembly was known to host speakers advocating women’s rights.

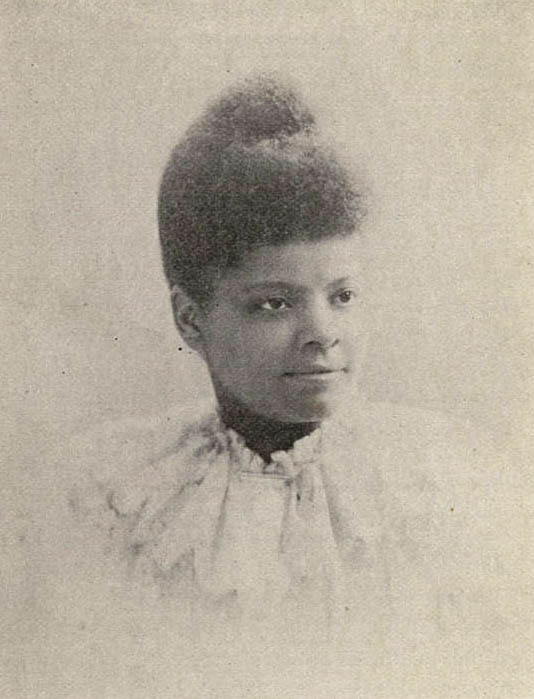

Ida B. Wells, a native of Memphis who was a journalist, feminist, and civil rights activist became one of the most well-known African American women of the nineteenth century. Library Collection, Tennessee State Library and Archives , ID# 33904.

The members of these organizations consisted of middle class women such as Lucy Tappan Phillips. Educated at Fisk University, she served as the first president of the WCTU chapter for Black women, with college classmates of hers serving as the other officers in that organization. Schoolteacher Florence P. Cooper, the president of the Coterie Migratory Assembly, was also a Fisk alumni.

Unfortunately, despite the efforts of Black women to aid in the suffrage cause, restrictive measures often greeted them at the polls. As one editorial writer for the Baltimore newspaper, the Afro-American, complained sarcastically, “It has been a very easy matter to disqualify a male Negro applicant for certificate to vote. It will be just as easy to disqualify the female Negro applicant. And thus we take another step in the great work of making the world safe for democracy.”

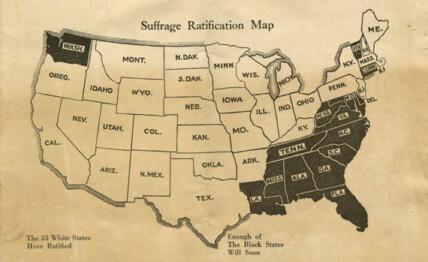

In fact, concerns over the enfranchisement of Black women had been a major obstacle for suffragists trying convince anti-suffrage citizens to support the Nineteenth Amendment. In one letter, U.S. Senator Kenneth McKellar, an ardent advocate of women’s suffrage, tried to assuage the fears of white southerners, “The negro men do not vote in the South and the negro women will not either, except occasionally some of them but if their votes ever become a menace to the white race in any way the white people of the South will take care of them in the future just as they have in the past.”

Even in Memphis where large numbers of African Americans could vote, local political boss E.H. Crump wanted Jim Crow measures such as poll taxes applied to Black women voting in Tennessee.

In the end, the exclusion of African Americans, especially Black women, from the crusade for women’s suffrage tainted the movement and limited what the Nineteenth Amendment was able to achieve. The willingness of white suffragists like Susan B. Anthony, Carrie Chapman Catt, and others to accommodate and compromise with bigotry while fighting for equality invites criticism; though at the time, it may have hastened ratification.

ITEMS FROM THE COLLECTION