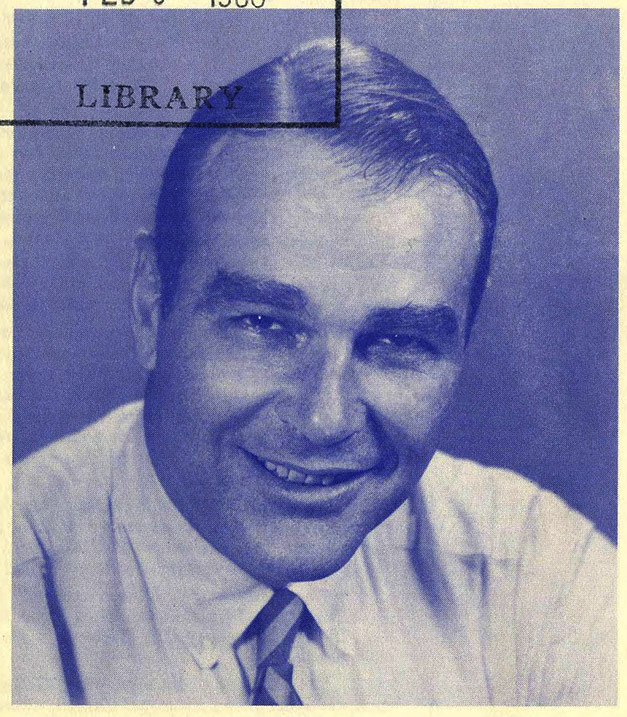

“Henry Loeb for Mayor”. See the full brochure on DIG Memphis

Either rightly or wrongly, Mayor Henry Loeb III has been blamed for creating the toxic environment where Martin Luther King Jr. was shot to death by an assassin at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis on April 4, 1968. It was Loeb’s obstinate refusal to agree to a dues checkoff for the union that allowed the strike to balloon into a national news story that attracted the attention of King and other civil rights leaders. As one citizen wrote in an April 9 telegram to the mayor, “Because of your stubbornness our city’s problem has been exposed to the entire nation.” In more telegrams from about the same date, other citizens called outright for the mayor to resign. For both white and black Memphians, Loeb had become a lightning rod for the racial issues surrounding the strike. And because of this, he needed to be the one to lead the climb down. As one East Memphis couple wrote to the mayor on April 8,“We are well educated, well paid white American Presbyterians…We are life-long Southerners and Memphians. We voted for you last election, but you must now realize that we and a thousand people like us think you are wrong. History has thrust upon you the opportunity to do a great deed and you have blown it because you could not find the right answer. The workers have won the strike; the white men of this nation have been overcome by Dr. King’s death. Will you join us in a surrender that can yet be honorable.”

Born into a wealthy and socially prominent family in Memphis, Loeb’s upbringing made him blind to the hardships facing many of the striking sanitation workers. During his youth, he attended Phillips Academy and Brown University, both elite schools in the northeast. As for the family fortune, Loeb’s grandfather had started a very successful laundry business, and by the time Henry became active in political life, the business had grown into a small commercial empire, employing hundreds of people in Memphis. Advertisements for Loeb barbeque joints and laundry cleaners appeared regularly in two prominent local papers: the Commercial Appeal and the Press-Scimitar. All of this privilege and financial security made it difficult for Henry Loeb to understand the precarious existence of the men working for the city sanitation department.

During his early political career, Loeb positioned himself as a vocal opponent of integration. Serving as public works commissioner starting in 1956, Loeb got himself elected to his first term as mayor in 1959 declaring during the campaign, “I would fight any integration order all the way.” Further, he publicly tried to prevent the election of black politician Russell Sugarmon as public works commissioner. This history made it easy for the black community to portray Loeb as a symbol of white oppression during the height of the strike. One of the chief mediators during the strike, Rabbi James Wax, put it this way:

“The negro people of the city resented Mayor Loeb and they resented the white people who had elected him to office. I am convinced (and this is an opinion) that another Mayor, free of racial discrimination, would not have encountered these difficulties. The strike was a protest not just against social injustice but an expression of hostility against Mayor Loeb whom they regard as an adversary.”

As a city, Memphis has had the blame for King’s death laid at it’s doorstep, and within the history of Memphis, Henry Loeb has been forced to bear a similar burden. Even within his life, Loeb seemed to understand that. Having trouble sleeping the night after King’s death, Loeb sat down at a typewriter to write a friend about the recent events:

“After what happened last night, George, this city has certainly had a tragic happening in our midst. Like him or not, admire him or not, no one has the right to take another man’s life, and I am simply shocked, and grieved that it could happen here.”

Loeb never again sought political office, and within a few years of the end of his mayoral term in 1971, he left Memphis to settle in Forrest City, Arkansas. It was there that he lived out the remainder of his life, making periodic trips back to his hometown.

Byron Wise to Henry Loeb, April 9 1968. Box 238, Folder 8. Papers of Henry Loeb III. History Department, Memphis Public Libraries, Memphis, TN.

Joseph P. Massey to Henry Loeb, April 9 1968. Box 238, Folder 8. Papers of Henry Loeb III. History Department,Memphis Public Libraries, Memphis, TN.

George B. Leon to Henry Loeb, April 8 1968. Box 238, Folder 8. Papers of Henry Loeb III. History Department, Memphis Public Libraries, Memphis, TN.

Henry Loeb to George E. Belote Jr., April 6 1968. Box 238, Folder 7. Papers of Henry Loeb III. History Department, Memphis Public Libraries, Memphis, TN.

Mary T. Robinett to Henry Loeb, April 9 1968. Box 238, Folder 8. Papers of Henry Loeb III. History Department,Memphis Public Libraries, Memphis, TN.

Rabbi James A. Wax to Rabbi Richard G. Hirsch, May 29 1968. Box 5, Folder 6. Rabbi James A. Wax Collection. History Department, Memphis Public Libraries, Memphis, TN.