“Maxine Smith” The M Files, DIG Memphis.

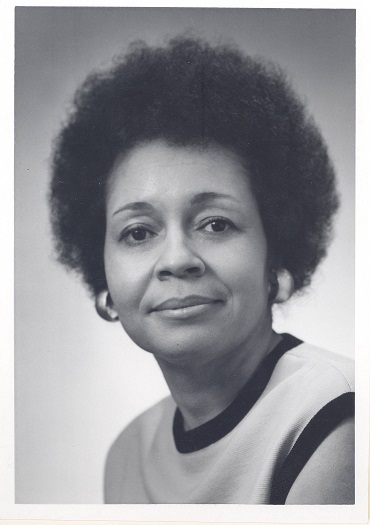

Maxine A. Smith

(1929-2013)

During the 1960s, the Civil Rights Movement proceeded in fits and starts. Throughout the country, and especially in the South, direct action against the old forces of segregation and discrimination occurred at in increasing clip. Strikes, sit-ins, and marches arose with regularity across cities and towns nationwide. Until 1968, however, Memphis remained a quiet metropolis inasmuch as no major disturbances garnered news coverage. Severe problems were papered over by the Jim Crow political rhetoric of Memphis being a “Place of Good Abode.” Nevertheless, changes had been taking place in the River City, and Maxine Smith drove much of these reforms.

Activists and union officials from outside Memphis, such as P.J. Ciampa and Jerry Wurf have received coverage as great influencers of the Sanitation Strike, yet Memphis’ own residents are who actually sustained the Strike and transformed it from a labor issue and merged it into the grand narrative of the Civil Rights Movement. A huge influence on this transformation was Maxine A. Smith, a Memphis native who served as the Executive Secretary of the local branch of the NAACP.

Smith, thirty-eight years old in the winter of 1968, was already a locally well-known leader by the time of the Sanitation Strike. While a young girl, she experienced the dehumanization of discrimination while visiting her sick father in a hospital. The hospital staff would not call her father by the customary title “mister” when addressing him. A graduate of Booker T. Washington High School in Memphis, and then obtaining a BA in biology from Spelman College in Atlanta, she became acquainted with Martin Luther King, Jr. while he pursued undergraduate studies at Morehouse College. She acquired a master’s degree in French from Middlebury College in Vermont and desired further graduate studies from Memphis State University but could not enroll due to her race. While teaching college courses in Texas, she met her future husband, Vasco Smith. They returned to Memphis to set up their household; he as a dentist, and she as a political force. She joined the local NAACP chapter, led by Jesse Turner, and as the membership chairperson, boosted the local chapter’s membership from a few hundred to over 3,000 in two years. She assisted the thirteen school children who desegregated the Memphis public school system in 1960. Her name and influence garnered respect nationwide. She was one of the last people Medgar Evers spoke with before his murder in June 1963.

When she was arrested after the March 5, 1968, sit-in at City Council chambers, she experienced the dehumanizing treatment noted in the “Sit-In Staged at City Council Protestors Arrested” article. In summary, in a personal replay of the past injustice experienced with her father, she was repeatedly called by her first name while being processed in the Memphis Jail, even after requesting to be called Mrs. Maxine Smith. She wrote a letter to Police and Fire Director Frank Holloman demanding that the officers responsible be fired and that such practices cease immediately. The Commercial Appeal reprinted portions of this letter to readers, with Holloman responding with calls for the NAACP to help increase a “better understanding in the community.” Smith, along with NAACP leadership and members, pressured the Strike’s leaders to pursue an increasingly independent path away from the AFSCME leadership. They saw the Strike a more of a black issue rather than a union/labor issue. This increased tension with union leaders such as Jerry Wurf and T.O. Jones who wanted to keep the Strike strictly a labor conflict. However, Smith and the NAACP maintained their line of reasoning. They persuaded Wurf who ultimately came to the conclusion that the Memphis Sanitation Strike was an indivisible knot of race, class, and labor issues.

Maxine A. Smith remained a key player during the Sanitation Strike, even as it reached the dénouement in April. On April 4, 1968, she was on her way to a dinner with Dr. King at the Rev. Samuel “Billy” Kyles home when she found out about Dr. King’s assassination. She continued to be an important force in local politics after the strike concluded. She orchestrated further actions promoting educational integration. From 1971 until 1995 she was elected to the Memphis Board of Education, culminating in her becoming the president of Board in 1991. She was nationally recognized by numerous awards for promoting civil rights in the field of education.

Beifuss, Joan Turner. At The River I Stand. Memphis: St. Luke’s Press, 1985.

Honey, Michael K. Going Down Jericho Road: The Memphis Strike, Martin Luther King’s Last Campaign. New York : W.W. Norton and Company, 2007.

“Protesters Plan City ‘Phone-In’.” Commercial Appeal, February 16, 1968.

“No ‘Impropriety’ Found in Police.” Commercial Appeal, March 14, 1968.

“NAACP’s Help is Solicited By City.” Commercial Appeal, March 24, 1968.

Letter From Maxine Smith to Holloman Concerning Her Arrest. Civil Rights Collection, DIG Memphis.

The HistoryMakers. “MAXINE SMITH.”